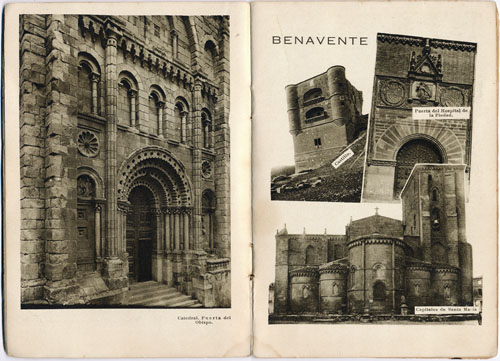

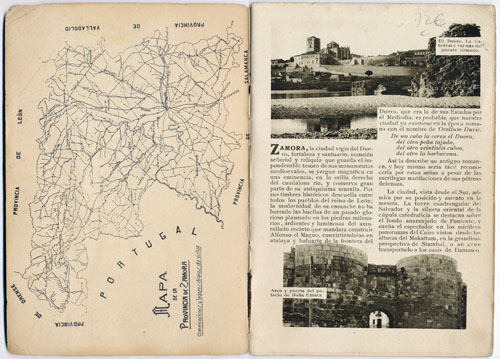

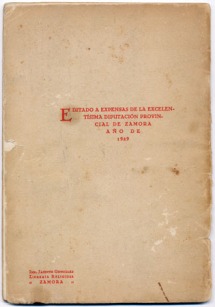

Every year, in the beginning of November, book-sellers from Granada and other parts of Andaluzia gather around Fuente de las Batallas, in the city’s centre. In this used-book fair, you may buy, for two or three euros, some of the most representative works of the most representative authors of the 20th century’s Spanish literature, like Lorca, Cela, Delibes, Marsé or Blasco Ibañez. Amongst these books, you may also find photo-related items, such as postcards, old prints and photo-books. Some of the most interesting objects are the old books published by government agencies, or at the expenses of those agencies, with the aim of promoting regions and historical monuments of Spain. For instance, if you’re lucky, you may find a pristine copy of the Avila’s tourist guide, with text by the Nobel prize-winner Camilo José Cela and photos by the famous Spanish photographer Francesc Catalá Roca. Or something like this guide to the city of Zamora, printed and published in 1929, with texts in Spanish, French and English.

-

Search It!

-

Recent Entries

- Collecting (17) – Zamora

- The Ceremony of Innocence is Drowned

- Collecting (16) — Trilogia (Trilogy)

- Photographing, Aging and Dying

- Words and Photography (Mark Kurlansky)

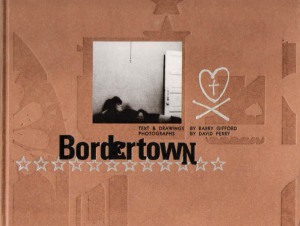

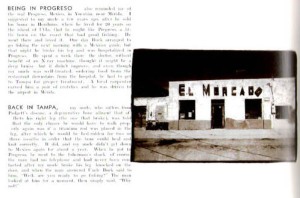

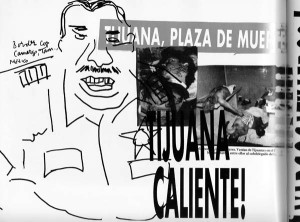

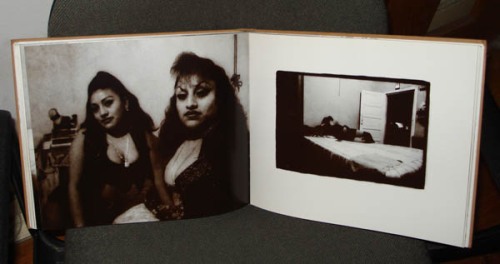

- Collecting (15) — Bordertown

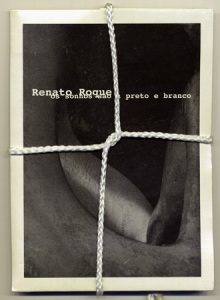

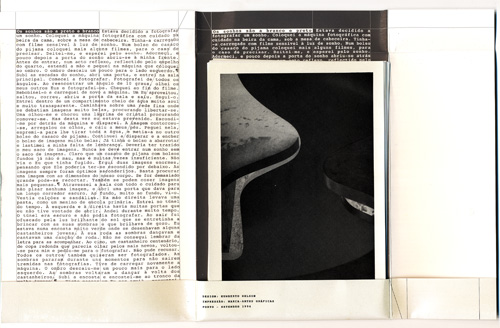

- Collecting (14) – Renato Roque’s Dreams

- Collecting (13) – Diapositives

- Behind carte-de-visite

- Words and Photography (Peter Handke)

-

Links

- A Arte da Fuga

- A Origem das Espécies

- A Photography Blog

- ABC do PPM

- Abrupto

- Afonso Azevedo Neves

- Alexandre Pomar

- Ana Pereira

- Aperture

- APPh

- Artcapital

- Arte Photographica

- Asian Photography Blog

- Atalaya

- Atlântico

- Ópera…

- Bio-inspired Computation

- Blasfémias

- Blue Lounge

- Buda@Peste

- Cachimbo de Magritte

- Carlos Lobo

- Carlos M. Fernandes

- Cinco Dias

- Combustões

- Contra a Corrente

- Crítico

- Desenhos com Luz

- Devaneios Desintéricos

- Dvafoto

- Estado Sentido

- Eternas Saudades do Futuro

- favacal

- Fugas

- Fundamentos da Passagem

- Geneura

- Grand Monde

- Illigal

- Insónia

- Kameraescura

- Kameraphoto

- Leonel Moura

- Machina Speculatrix

- Magnum Blog

- Miguel Coelho

- Miguel Santos

- Na Cozinha

- Na Cozinha

- Nafarricos

- Núcleo de Arte Fotográfica

- No Mundo

- No Mundo

- Nuno Castelo-Branco

- O Insurgente

- O Observador

- P4PHOTOGRAPHY

- Pente 10

- Perpetuum Mobile

- Photography

- Photography Blog

- Plexu

- Portugal Contemporâneo

- Portugal dos Pequeninos

- Pumba in Japan

- Rabbit’s Blog

- Random Precision

- Rua da Judiaria

- Sais de Prata e Pixels

- Small Brother

- Stick Me

- Super Flumina

- The Photobook

- The PhotoBook

- theartsight

- Ultraperiférico

- Vento Sueste

- WordPress.com

- WordPress.org

- Y Viva España

Alexander Gardner

Alexander Gardner